NorthSec 2018 - Mars Analytica

In May 2018, the NorthSec conference and its on-site CTF competition were held. Once again the competition was awesome, the challenges were very diverse and the infrastructure was well configured.

One of the reverse engineering challenges was a program called MarsAnalytica. This challenge remained unsolved at the end of the CTF. This binary was worth a lot of points and I think it was the right amount of points due to the time one would have to spend to solve it.

This blogpost will discuss how I solved it.

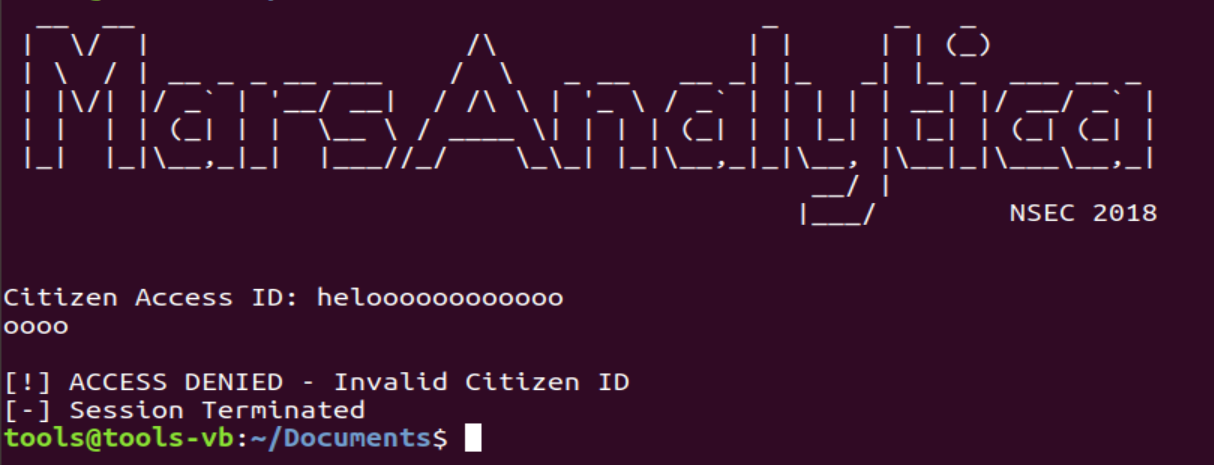

The government has hired a specialized data brokerage, collection, and analysis firm known as Mars Analytica to assess the societal worth and risk of its citizens in preparations for the colonization of Mars. Publicly officials are denying this, but you got your hands on their analysis software. Find a way to log in with a cleared citizen id and expose the Mars Analytica firm's true purpose.

Before attempting to reverse a binary, it is always good to take a look at the low-hanging fruits: the file format, the size, the strings… At first sight the binary didn’t seem to be too big. Running the file utility against it indicated that it was compressed with UPX. The command output also indicated that it is a stripped ELF x86-64 binary. After having unpacked the ELF binary, the size grew to almost 11M :O No useful strings are present in the binary.

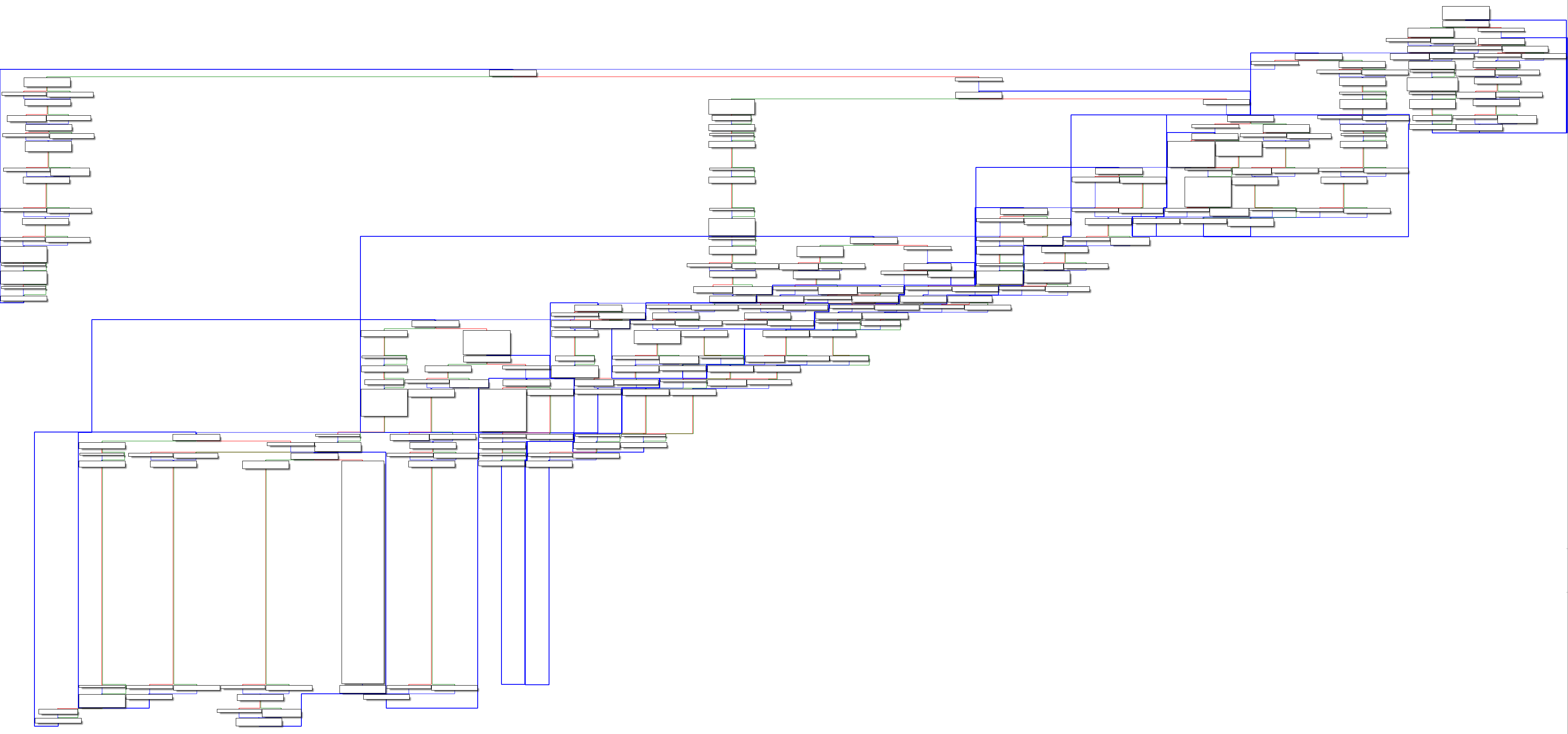

After having opened the binary in IDA and let the autoanalysis complete (which took some time), the navigation bar didn’t look reassuring.

Looking at the main function revealed a lot of weird stuff are going on:

- a very large stack frame is created (0xBA4A8)

- the classic call combination time/srand is present but the rand function is not even imported

- 5 different large arrays of bytes are copied to the stack

- some weird calculations based on the arrays copied is happening

- the function ends with a push/ret

Just out of curiosity, I took a look at the disassembly following the main function. One could see that the same weird computation is present in the following (undefined) functions. Moreover, most of these functions either ends with a push/ret or a jmp rax.

This code construct reminded me of a virtual machine where each handler computes the address of the next handler (like a distributed dispatch or direct-threaded code).

This can be further verified by dynamic analysis using a debugger such as GDB but beforehand, once again: low-hanging fruits.

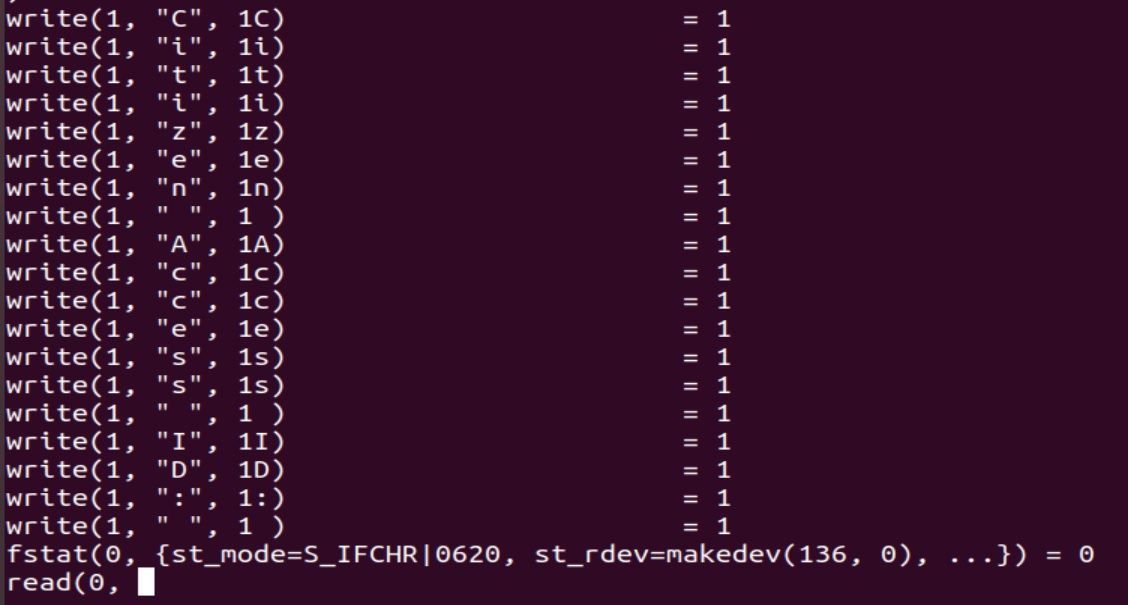

A little bit of strace could give an overview of how the binary behaves.

I guessed that all the “write(1,char,1)” lines were in fact calls to the putchar function. A good thing to do also is looking at the cross-references. There are 861 calls to the putchar function which meant that there are probably some redundant handlers.

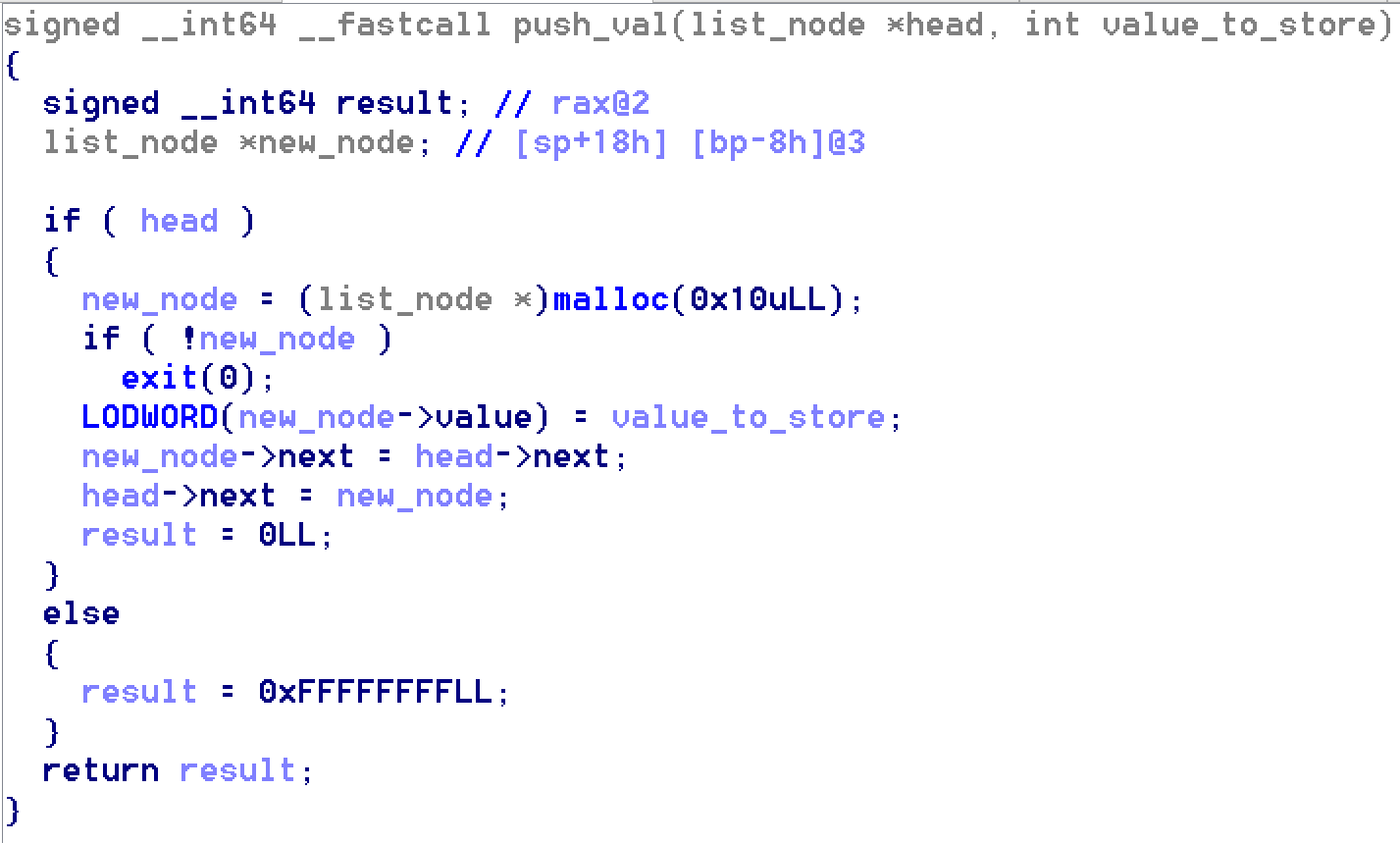

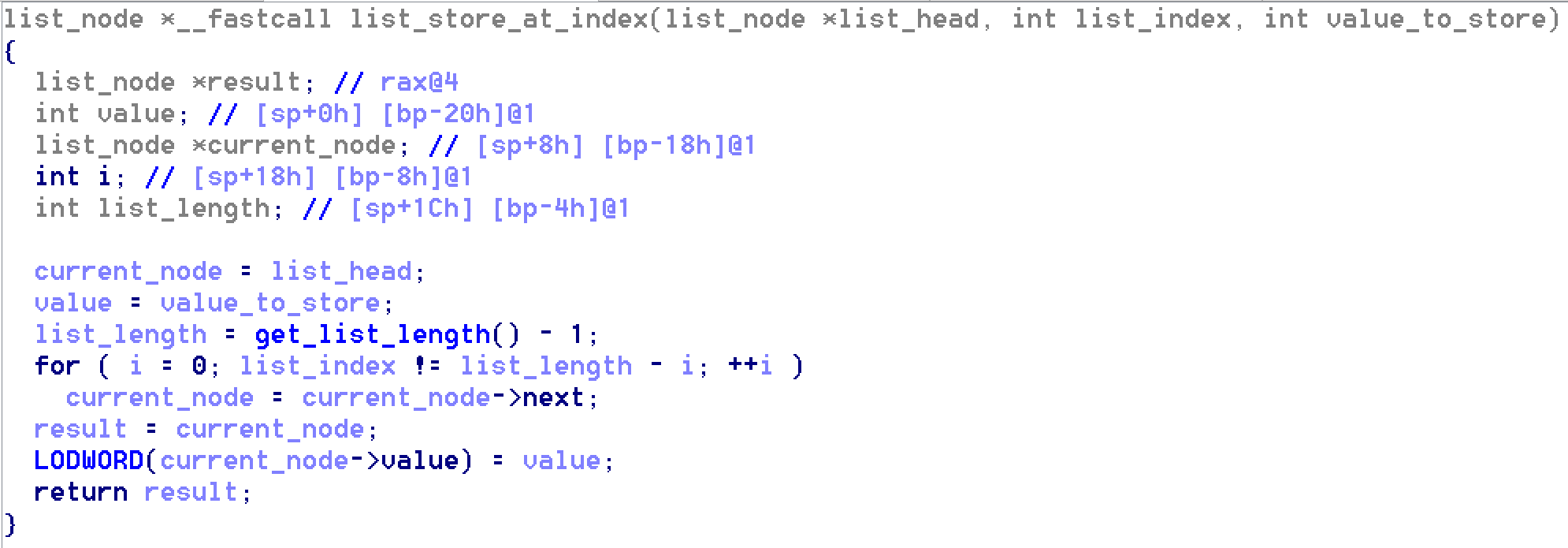

Another interesting function to look at was the malloc function. The first cross-reference took me to a function which seemed to be a list insertion algorithm.

Interestingly enough, there are 1178 cross-references to this function.

A hunch told me to look at the free function. As expected the first cross-reference to the free function is a routine which implements a list removal algorithm. There are 1276 cross-references to that function.

At first sight it looked like that virtual machine might be stack-based.

Then I started debugging the binary with GDB but it didn’t really helped me except to confirm that each handler was indeed in charge of computing the next handler address.

At that moment I thought that I had enough information to start reversing.

In order to implement a disassembler for the VM I had to focus on the weird computation first to be able to compute the next handler. The main function is the right entrypoint to gather information about the VM initialization. As mentioned earlier the 5 arrays are essential to the handler computation. After renaming some variables, following the computation dynamically, diffing with other handlers, it was possible to understand and reimplement the routine.

mov [rbp+var_65F40], 0

mov rax, [rbp+var_65F40]

mov edx, eax

lea rax, [rbp+tab2]

mov [rbp+ptr_cpy_e50140], rax

lea rax, [rbp+tab1]

mov [rbp+ptr_cpy_e4dc00], rax

mov [rbp+var_908B0], edx

mov rax, [rbp+ptr_cpy_e4dc00]

mov [rbp+var_5DB68], rax

mov eax, [rbp+var_908B0]

mov [rbp+var_908AC], eax

mov eax, [rbp+var_908AC]

imul ecx, eax, 7AAh

mov edx, 3700C083h

mov eax, ecx

imul edx

sar edx, 9

mov eax, ecx

sar eax, 1Fh

sub edx, eax

mov eax, edx

imul eax, 94Fh

sub ecx, eax

mov eax, ecx

cdqe

lea rdx, ds:0[rax*4]

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DB68]

add rax, rdx

mov eax, [rax]

mov rdx, [rbp+ptr_cpy_e50140]

mov [rbp+var_5DB60], rdx

mov [rbp+var_908A8], eax

mov eax, [rbp+var_908A8]

imul ecx, eax, 5A5h

mov edx, 3700C083h

mov eax, ecx

imul edx

sar edx, 9

mov eax, ecx

sar eax, 1Fh

sub edx, eax

mov eax, edx

imul eax, 94Fh

sub ecx, eax

mov eax, ecx

cdqe

lea rdx, ds:0[rax*4]

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DB60]

add rax, rdx

mov eax, [rax]

lea rdx, [rbp+tab4]

mov [rbp+var_5DB98], rdx

lea rdx, [rbp+tab3]

mov [rbp+var_5DB90], rdx

mov [rbp+var_908BC], eax

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DB90]

mov [rbp+var_5DB88], rax

mov eax, [rbp+var_908BC]

mov [rbp+var_908B8], eax

mov eax, [rbp+var_908B8]

imul ecx, eax, 259h

mov edx, 2F3BAFEDh

mov eax, ecx

imul edx

sar edx, 9

mov eax, ecx

sar eax, 1Fh

sub edx, eax

mov eax, edx

imul eax, 0AD7h

sub ecx, eax

mov eax, ecx

cdqe

lea rdx, ds:0[rax*4]

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DB88]

add rax, rdx

mov eax, [rax]

mov rdx, [rbp+var_5DB98]

mov [rbp+var_5DB80], rdx

mov [rbp+var_908B4], eax

mov eax, [rbp+var_908B4]

imul ecx, eax, 1D5h

mov edx, 2F3BAFEDh

mov eax, ecx

imul edx

sar edx, 9

mov eax, ecx

sar eax, 1Fh

sub edx, eax

mov eax, edx

imul eax, 0AD7h

sub ecx, eax

mov eax, ecx

cdqe

lea rdx, ds:0[rax*4]

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DB80]

add rax, rdx

mov esi, [rax]

mov rax, [rbp+var_65F40]

lea rdx, [rax+1]

mov [rbp+var_65F40], rdx

mov edx, eax

lea rax, [rbp+tab2]

mov [rbp+var_5DBB8], rax

lea rax, [rbp+tab1]

mov [rbp+var_5DBB0], rax

mov dword ptr [rbp+var_908CC+4], edx

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DBB0]

mov [rbp+var_5DBA8], rax

mov eax, dword ptr [rbp+var_908CC+4]

mov [rbp+var_908C4], eax

mov eax, [rbp+var_908C4]

imul ecx, eax, 7AAh

mov edx, 3700C083h

mov eax, ecx

imul edx

sar edx, 9

mov eax, ecx

sar eax, 1Fh

sub edx, eax

mov eax, edx

imul eax, 94Fh

sub ecx, eax

mov eax, ecx

cdqe

lea rdx, ds:0[rax*4]

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DBA8]

add rax, rdx

mov eax, [rax]

mov rdx, [rbp+var_5DBB8]

mov [rbp+var_5DBA0], rdx

mov [rbp+var_908C0], eax

mov eax, [rbp+var_908C0]

imul ecx, eax, 5A5h

mov edx, 3700C083h

mov eax, ecx

imul edx

sar edx, 9

mov eax, ecx

sar eax, 1Fh

sub edx, eax

mov eax, edx

imul eax, 94Fh

sub ecx, eax

mov eax, ecx

cdqe

lea rdx, ds:0[rax*4]

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DBA0]

add rax, rdx

mov eax, [rax]

cdqe

mov rax, [rbp+rax*8+tab5]

mov [rbp+var_5DBC0], rax

mov dword ptr [rbp+var_908CC], esi

mov eax, dword ptr [rbp+var_908CC]

movsxd rdx, eax

mov rax, [rbp+var_5DBC0]

add rax, rdx

push rax

jmp short locret_401149 ; 0x402335

locret_401149:

retn

The stack variable rbp-0x65f40 seemed to be the “program counter” because it is incremented everytime. Also its value is used as an index in the first array. The value fetched is then used as an index in the second array…

The following pseudocode might explain it better (using IDApython).

# get the arrays used by the dispatcher

tab1=[Dword(0xE4DC00+i) for i in range(0,0x253C,4)]

tab2=[Dword(0xE50140+i) for i in range(0,0x253C,4)]

tab3=[Dword(0xE52680+i) for i in range(0,0x2B5C,4)]

tab4=[Dword(0xE551E0+i) for i in range(0,0x2B5C,4)]

tab5=[Qword(0xE57D40+i) for i in range(0,0x56B8,8)]

# dispatcher function

# num is the value of VM.PC

def dispatcher(num):

global tab1,tab2,tab3,tab4,tab5

eax = tab4[tab3[tab2[tab1[(num*1962)%len(tab1)]*1445%len(tab2)]*601%len(tab3)]*469%len(tab4)]

edx = tab5[tab2[tab1[(num*1962)%len(tab1)]*1445%len(tab2)]]

return eax+edx

Looking at the first handler @ 0x402335, it starts to compute a number in the same fashion as the dispatcher code. The number is then passed to the function which implements list insertion. Finally the next handler is computed. As seen in the list insertion code, a pointer to the head is passed and is updated after insertion. I infered that the variable rbp-0x65f48 was the “VM stack pointer”. The start of the function fetches an immediate which is pushed. The handler @ 0x402335 is of the form “PUSH Immediate”.

The next handler to look at was @ 0x401b8f. It starts by popping (list removal function) one value off of the virtual stack, gets an immediate value and stores the popped value in a virtual stack variable indexed by the immediate value. For instance, at the beginning we have:

PUSH 0

PUSH 9

STORE SP[0]

If we split and keep track of the states we have:

PUSH 0 => SP[0] = 0

PUSH 9 => SP[0] = 0, SP[1] = 9

STORE SP[0] => SP[0] = 9

I concluded that this handler was of the following form:

STORE SP[Immediate Index]

Since the machine implements a stack machine it is really important to understand how values and pushed and popped. The astute reader would have probably noticed that it is also possible to access stack variables by index.

After reversing some more handlers I eventually got stucked because there were too many handlers (remember the 10M size?… ) and I saw some redundant handlers not to mention that a lot of them were very obfuscated.

At that moment I really thought about completely changing my way of solving the challenge because I would have needed to reverse too many handlers to implement a disassembler based on handlers start address.

Though reverse engineering really consists in finding/recognizing pattens, experiencing, repetition… so I went looking for patterns.

At some point I started to see a correlation between the calls a handler makes and the behaviour of the handler.

For instance, I knew that if a handler calls the functions pop_val, putchar and fflush then the handler just implements a putchar.

In order to take advantage of that, one need to gather the handler’s “cross-references from” and compare that list. The following code describes the process:

f_putchar=["pop_val","putchar","fflush"]

calls=[x for x in idautils.FuncItems(handler) if idaapi.is_call_insn(x)]

targets=list(map(lambda x: GetOpnd(x,0),calls))

if all(t in targets for t in f_putchar):

sys.stdout.write("putchar\n")

The next thing I noticed was the most important information.

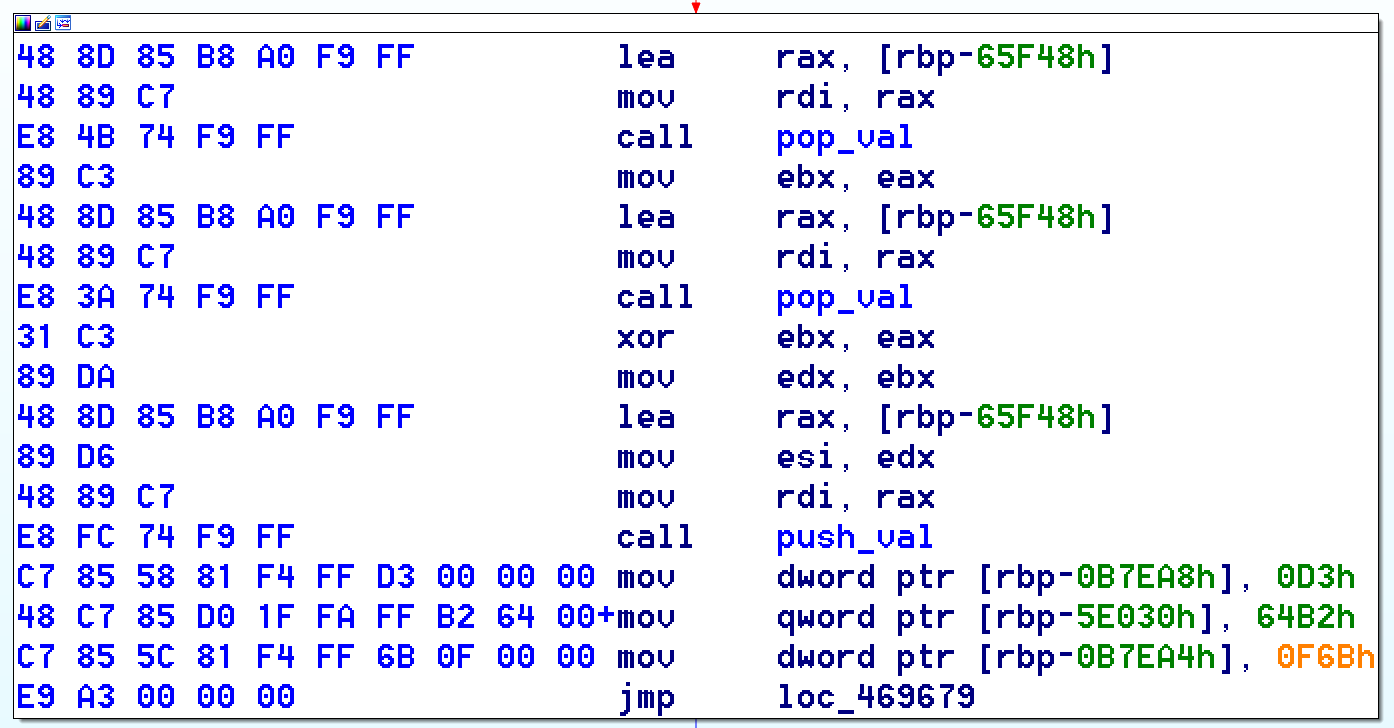

Some handlers are very complicated to understand due to their obfuscation but as the VM is stack-based, the code needs to access the stack variables and it does so by calling the pop_val function for example. The following images show the overview of a XOR handler and then its relevant code.

As one can see, that part is not obfuscated and it is pretty clear:

- two values are “popped” from the stack

- a XOR operation is made between the two values

- the result is pushed on the stack

This is clearly a weakness in the binary obfuscation and I decided to take advantage of it. To that end, one need to:

- make sure that a handler calls 3 functions (“pop_val” twice and “push_val”)

- retrieve the operation right after the second “pop_val”

The following code searches for the pattern:

0 call pop_val

…

17 call pop_val

22 operation

or the following pattern (for the div instruction)

0 call pop_val

…

17 call pop_val

…

30 cdq

31 idiv

operations={"xor":"xor","sub":"sub","imul":"mul","lea":"add"}

...

elif len(targets) == 3 and targets.count("pop_val") == 2:

operation=None

for caller in calls:

if GetOpnd(caller,0) == "pop_val" and caller+17 in calls:

mnem = GetMnem(caller+22)

if mnem in operations.keys():

operation=operations[mnem]

elif GetMnem(caller+30) == "cdq" and GetMnem(caller+31) == "idiv":

operation="div"

sys.stdout.write(operation + "\n") if operation is not None else unknown_handler(PC,targets)

Once again here I made a big assumption regarding the patterns I saw and I didn’t take into account false positives I could have had so I strongly advise against that technique.

Generally speaking, it is always better to come up with a more generic and a less pattern-based solution for reuse purposes but also to make the solution more resilient to broken patterns.

Another big assumption I made was using a linear sweep for the disassembly.

After putting the different techniques together and having crossed my fingers for the code not to break, I obtained the following assembly listing:

...

0x6f2: 0x401f62: load[0x00000009]

0x6f3: 0x401f62: load[0x0000001b]

0x6f4: 0xbde28a: mul

0x6f5: 0x401f62: load[0x00000017]

0x6f6: 0x401f62: load[0x00000012]

0x6f7: 0x402ab2: swap

0x6f8: 0xbdf48d: sub

0x6f9: 0x401f62: load[0x0000001d]

0x6fa: 0x402ab2: swap

0x6fb: 0xbe059f: xor

0x6fc: 0xbe1957: mul

0x6fd: 0x402335: push 0x00003fcf

0x6fe: 0xbe2b48: cmp

...

The code displays the banner character after character and then asks for a “citizen id”.

The characters are put in the virtual stack but they are not next to each other. Instead the characters are kind of rearranged by the following list:

7,8,13,15,16,26,27,22,21,4,18,28,23,29,9,1,25,30,17

It means that the first character will be put in the 7th virtual stack variable, the 2nd character at the 8th position and so on.

After that some computations between characters are made and the result is compared to hardcoded values. The verification algorithm is based on several equations.

For instance the first equation is:

(buf[14] * buf[6])*((buf[12]-buf[10])^buf[13]) - 0x3fcf == 0

After having gathered all the different equations I used z3 to solve them. The code is pretty straightforward. First one need to declare all the characters, add a constraint to make sure the character is printable and then add the equations.

from z3 import *

solver = Solver()

# Flag order

order=[7,8,13,15,16,26,27,22,21,4,18,28,23,29,9,1,25,30,17]

flag={}

for i in order:

flag[i] = BitVec("c_%d" % i,8)

#char constraints

for k in flag.keys():

solver.add(flag[k] >= 32, flag[k] <= 126)

#equations

solver.add((flag[9] * flag[27])*((flag[23]-flag[18])^flag[29]) == 0x3fcf)

...

solution=''

if solver.check() == z3.sat:

model=solver.model()

for i in order:

solution+=chr(model[flag[i]].as_signed_long())

print solution

The scripts yields the following result:

q4Eo-eyMq-1dd0-leKx

The different scripts can be found here.

I first tried to use Pin which thanks to the instruction counter helped me to get the correct number of characters the challenge expects. I then wanted to use Triton but I had some memory problems with Pin also it was quite slow (not to mention that I was doing this in a VM).

Also some handlers push a letter which is computed through obfuscated code. I took the decision to ignore that even if it makes the assembly kind of incomplete…

This binary was quite challenging as it features several obfuscation techniques such as code virtualization, dead code, bogus control flow, opaque predicates, direct-threaded code… I want to thank Towel for this incredible challenge and a shoutout to Wakfu for the few pointers he gave without spoiling all the fun.

The solution is far from being the best but I think as it is a CTF challenge this IDA api-based solution is acceptable as I took advantage of the VM characterics. Different approaches could be taken here such as:

- using symbolic execution and the knowledge of the VM structure to resolve each handler

- using DSE

- using taint analysis

Actually I plan to come back with a more elegant solution so stay tuned :)